In “What is the Biggest Threat to Fed Independence?” David Beckworth actually addresses something that is more analytically interesting, “fiscal dominance” of monetary policy. The switch comes because Beckworth conflates fiscal dominance with loss of central bank independence.

But first, what is “fiscal dominance, a phrase much used always as a pejorative? Beckworth has a clean definition, “the moment when fiscal pressures become a true macroeconomic constraint, that is, when monetary policy is no longer focused on price stability, but on keeping the federal government solvent.”

It is a clean definition, but not without its problem in that it implies that a central bank is or should be focused exclusively on “price stability.” But that ignores the explicit “dual mandate” of the Fed implicitly of most other central banks (except, in practice, the ECB before 2010). In the context of a dual mandate monetary policy should never be focused on “price stability” alone but the degree of price stability (rate of inflation) that maximizes employment or real income.

Stated as a central bank choice between price stability and government solvency, an infinitely elastic criterion “fiscal dominance” could happen anytime or never. This, however, would drain the concept of any economic content. Let’s approach this by exclusion.

In “monetary dominance” times a central bank’s target rate of inflation and deviations from it depend on

a) the size and frequency of sectoral shocks that require changes in relative prices and

b) the degree of downward “stickiness” of certain prices that requires inflation to “lubricate toward relative price adjustment.

Within wide limits the fiscal deficit does not affect the income maximizing inflation target, only the “interest rate” (the vector of monetary policy instruments) needed to achieve it.

Perhaps a better way to think about “fiscal dominance is the point at which fiscal policy comes to affect the income maximizing rate of inflation the central bank seeks. Taking account of the differential effect that high interest rates can have on saving and investment and possibly sectorial effects (residential and commercial development vs other sectors), the central bank might conclude that the distortions arising from high inflation are less than those arising from the high interest rates that would be required to maintain a pre-established target. This, however is not the same as and need not be the result of any _political_ pressure on the central bank or challenge to its independence in arriving at its judgement on the setting of monetary policy instruments. The central bank would “just” be independently carrying out its mandate to execute income maximizing inflation in the same way as it reacted to a sectoral shock.

This should be contrasted with fiscal dominance without central bank independence described by Beckworth:

From 1942 to 1951, the Fed operated under an explicit agreement with the Treasury to cap interest rates across the yield curve to support wartime financing. Short-term rates were held at ⅜ percent, and long-term rates were pegged at 2.5 percent. …To maintain those caps, the Fed stood ready to buy Treasury securities in whatever quantity was needed, effectively monetizing fiscal policy. The Fed, in short, subordinated its inflation objective to the government's funding needs …

But then Beckworth muddies the water with the following:

We also caught a glimpse of fiscal dominance during the COVID-19 crisis. As George Hall and Thomas Sargent have documented in a series of papers, the Fed rapidly expanded its balance sheet to absorb a surge of Treasury issuance, support financial markets, and hold rates near zero. For a time, it looked less like the Fed was leading policy than financing it. Fed officials may bristle at the idea that they were operating under fiscal dominance during the pandemic. However, the COVID crisis was a major public health war and fiscal dominance was arguably necessary.

No. Large purchases of Treasury debt is not “fiscal dominance.” The Fed was on strong grounds to pursue higher inflation at least until mid 2021. It was not subordinating its inflation objective to Treasury needs. To say, “fiscal dominance was necessary” betrays Beckman’s view that any inflation in excess of some pre-established level cannot be part of a monetary dominance regime.

All of this is just dancing around the mastodon in the room, the truly enormous tax cuts and deficits that Congress seems poised to inflict going forward, tax cuts that could indeed usher in fiscal dominance and, worse, financial repression to contain the inflation.

This prospect leads Beckman to quote favorably, “Ultimately, the US may face a political choice between reforming entitlement programs and tolerating high inflation and financial backwardness.”

Or – just a wild Radical Centrist thought – the choice to _pay for_ entitlement programs with tax revenues (hopefully revenues from a consumption VAT).

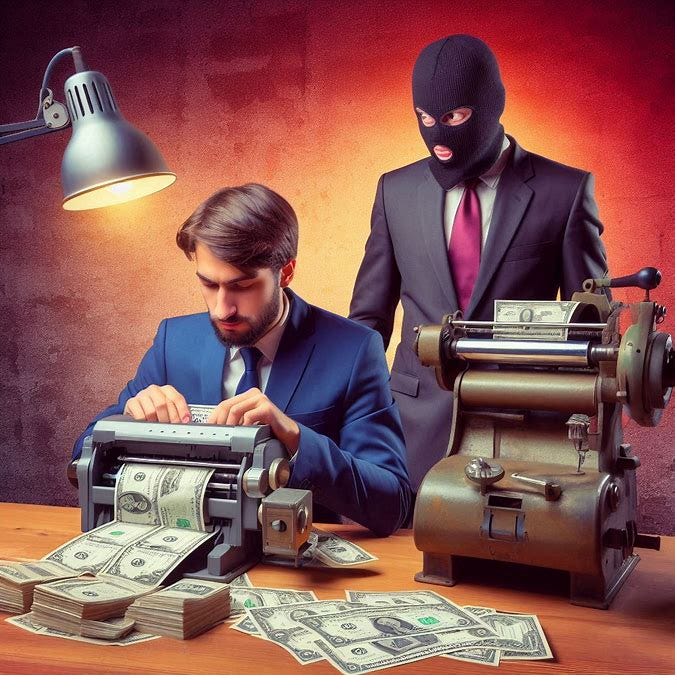

Image prompt: Central banker printing money under the stern gaze of an armed goon

[Standard bleg: Although my style is know-it-all-ism, I am aware that I could be mistaken or overstate my points. I would, therefore, welcome comments on these views.]

The REAL problem is that people tend to be stupid about money; and they're EVEN WORSE if it's government money.

As I told a British guy, in the US both major parties consider individuals earning 3x the median income to be part of "the struggling middle class".